Provocative new academic review of Appetite for America in The Journal of American Culture

Blurb:

“Lively and engaging … a detailed, extensively researched and fascinating picture of the Fred Harvey empire. There is already a large body of scholarship on the Fred Harvey Company … [and] several short biographies of Harvey … but this is the first comprehensive study of the company, its major characters, their motivations and the role each played in the rise and fall of the empire. … Fried is a journalist by training, and Appetite for America is an anecdotal history for the general reader … The author clearly had a lot of fun researching and writing this book. … I stayed up half the night reading it and … loved every delicious, untroubling moment of it.”

–Joy Sperling, Denison University

Journal of American Culture

Full Review:

The Journal of American Culture, March 2011

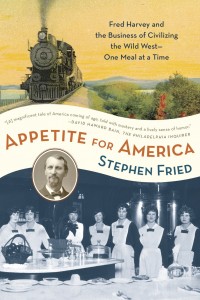

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire that Civilized the West

Stephen Fried. New York: Bantam Books, 2010.

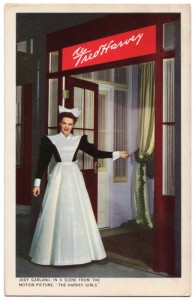

In January 1946, MGM released The Harvey Girls, a sweeping musical extravaganza starring Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Angela Landsbury and Cyd Charisse. It was a feel-good tale of good versus evil, the taming of the west and a flock of Harvey Girls, waitresses in Fred Harvey’s famous railroad eating houses along the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe (AT&SF) line. The Girls, dressed in vaguely nun-like black-and-white uniforms, redeem the ‘‘loose women’’ of the fictional town of Sandrock and civilize the men. The movie was short on plot but delivered elaborate song-and-dance numbers and pure escapism. Its lead song, ‘‘On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe’’ won an Oscar and the movie was one of the highest grossing films of its time. Today, few of us know the name Fred Harvey, why MGM would make such a high budget movie about a restaurateur and his waitresses, or why it was such a hit.

Fred Harvey was as well known in his time for his restaurant management systems, luxury hotels in the southwest, and the Fred Harvey brand as his contemporary Henry Ford was for his production systems, Frederick Taylor for his ‘‘scientific manage-ment,’’ or later Walt Disney for his theme park. But Fred Harvey’s success rose and fell with transcontinental passenger train travel. Although Harvey died in 1901, the Fred Harvey Company, under his son Ford Harvey’s management, emerged as a service industry empire that collapsed after automobile and airline travel eclipsed luxury train travel after World War II. Today, the Fred Harvey Company, absorbed by the Xanterra Corporation, still holds the concession rights to the Grand Canyon and several southwestern national parks.

Fred Harvey’s success was built on his consistently high level of service and mythologizing of the Fred Harvey brand. Harvey reinvented the restaurant stops along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line in the southwest at a pivotal time, when independent rail- roads battled for control of territory across the United States. The Santa Fe’s dominance was based in part on its widespread advertising though visual imagery: prints of famous works of art such as Thomas Moran’s view of the Grand Canyon, calendars distributed to almost a million people annually, and the relentless advertising of Fred Harvey’s restaurants and hotels along the line. Harvey’s restaurants were clean, formal, and provided standardized good food delivered in record time to accommodate the railway timetable. Harvey’s major contribution to American culture was the invention of fast high-quality food service. Additionally, he populated the southwest with good, clean, polite, usually malleable and marriageable young girls; indeed, Harvey was frequently described by contemporaries as the man who really ‘‘civilized’’ the west.

In its day, the Fred Harvey Company’s reputation drew monarchs, presidents, and movie stars to hotels such as El Tovar on the southern rim of the Grand Canyon and La Fonda in Santa Fe. The Fred Harvey Company promised his customers luxury, glamour and the fantasy of rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous and offered the Harvey Girls financial independence, escape from the grime of big-city or the confines of small-town America to a new, reinvented life in the west, and the possibility of finding a rich western husband.

Harvey’s first restaurants were served by African-American waiters; indeed railway dining cars and sleeping accommodations nationwide were so-staffed for decades. For still obscure reasons, at the end of the nineteenth century, Harvey switched his entire serving staff to young women. In Appetite for America, Stephen Fried suggests that Harvey sought to protect African-American men from the regular beatings or worse that they endured in the west (86), but it is more likely that young women cost less, were more malleable, more easily regulated, and exerted a calming force on locals.

Harvey’s solicitations for Harvey Girls were published in newspapers and magazines in the east and Midwest; Harvey Girls were young, single, and of good moral character. Each was required to sign a contract agreeing to stay in Harvey’s employ for the full extent of their six-month term, to live in the highly structured Harvey dormitories, and to remain single. Harvey Girls were subjected to inspection daily: they wore perfectly maintained uniforms to work, tied their hair back simply, and wore no makeup.

In his restaurants, Harvey demanded standardized recipes, coffee made to strict specifications that went as far as daily testing and adjustment of the alkalinity of water used, bread cut precisely in 3/8in. slices, and orange juice squeezed only when ordered. Harvey invented the famous ‘‘cup-code’’ for faster beverage service. If coffee was ordered, the cup remained in the saucer; for milk it was inverted on the table and set beside the saucer; for iced tea it was inverted and leaned against the saucer; and for tea it was inverted on the saucer with the handle pointing in one of three directions depending on whether black, green, or orange pekoe tea was ordered. Harvey’s business model was equally terse and efficient. He insisted after his retirement that a family member and tight inner circle of advisors lead the company and that they maintain twelve conservative business practices that included in addition to the concentration of the business in as few hands as possible, actively catching employees young, promoting exclusively from within, gradual and steady company expansion, and reinvest- ing company profits in the business.

Fried’s Appetite for America is a lively and engaging biography of the key players in the history of the Fred Harvey company. Fried presents a detailed, extensively researched and fascinating picture of the Fred Harvey empire. There is already a large body of scholarship on the Fred Harvey Company exploring the company’s connections to an emerging southwest tourist industry, its promotion of Native American art and crafts, its patronage of architect Mary Colter, and its close working relationship with the early anthropology in Santa Fe. There are also several short biographies of Harvey and his company, but this is the first comprehensive study of the company, its major characters, their motivations and the role each played in the rise and fall of the empire. Fried’s narrative sometimes meanders around the Harvey family and through cultural history, taking interesting side trips to discuss such topics as the debate over standardized time (97), the history of American postcards (197), or the origin of Walt Disney’s inspiration for his theme parks (394). Fried’s more than complete documentation sublimates his narrative’s agenda. Yet, Appetite for America eschews critical analysis and scholarly method in favor of spinning a good yarn; it avoids asking critical questions or engaging the debates about Fred Harvey or his business model.

Fried’s book describes the Fred Harvey Company’s rise to wealth and fame and its inevitable fall. Fried makes his characters human, despite the fact that Fred Harvey was by all accounts a dry, humorless individual. Fried is deeply sympathetic to Fred Harvey, and he makes some interesting comments about the battle for control of the company between Byron Harvey, Fred Harvey’s brother and his nephew Freddie Harvey. The decisions not to exploit automobile travel sites along highway 66, to capture middle-class markets for food and lodging, or to compete for airline concessions, which Freddie advo- cated before his untimely death in an airline crash, functioned in concert to undermine the health of the business as railroad passenger service diminished after the war. Fried notes with sad irony that the 1946 song about the AT&SF made more money than the railroad that inspired it (392).

Fried’s history is energetic and engaging, but includes no real analysis of the implications of the Harvey methods. I would have preferred to see Harvey compared and contrasted with his peers, Ford and Taylor specifically, who collectively ushered in a new age of consumer products, their production, and promotion. Fried also glosses over the more troubling questions of race and gender that permeate the Harvey story and which established the paradigm for the treatment of several generations of service workers. Harvey’s employment of a mostly female work force was a key factor in his economic success and might have been treated with less certainty that it was a good thing; Harvey Girls may have considered themselves part of an elite force, but they were also essentially indentured servants with few rights.

Fried is a journalist by training, and Appetite for America is an anecdotal history for the general reader. The catchy double entendre of its title is echoed in several chapter titles that include the awful puns, ‘‘Acute Americanitis,’’ ‘‘National Parking,’’ and ‘‘Heir Raising.’’ There are, in addition, ‘‘Freditor’s Notes and Sources’’ plus three appendices: a description of Fried’s own ‘‘Grand Tour’’ of extant Harvey institutions, a collection of recipes from ‘‘Meals by Fred Harvey,’’ and a list of Harvey hotels with the current state of (dis)repair. The author clearly had a lot of fun researching and writing this book. Appetite for America is not quite biography, not quite social history, not quite business history, but I stayed up half the night reading it and, as with The Harvey Girls, loved every delicious, untroubling moment of it.

—Joy Sperling, Denison University